- Part One of this series of blog posts introducing TypeScript and React is here.

It’s not too hard (any more) to get started with TypeScript and React. This post assumes that you know a little about JavaScript and a little about React—if you haven’t created an app already you can do it with create-react-app-typescript:

> npm install -g create-react-app

> create-react-app my-app --scripts-version=react-scripts-ts

> cd my-app

> npm start

The Component

Here’s an example component called, well, exampleComponent.tsx:

You’ll notice that this is almost the same as it would be in vanilla JavaScript, except for those type definitions.

Include it in App.tsx with this code:

import ExampleComponent from "./example/exampleComponent"; // use the "default" export

// OR: import {ExampleComponent} from "./example/exampleComponent"; // use the explicit export

// ...

console.log(count)} />

If you open the console and click on the button, you should see the counter increase.

Typing Props and State

When you create a Component class, you should create types for the props and the

state. Here we’re requiring that the caller provide the function onCounterIncrease, which takes the

current count number and returns nothing. The text variable is a string, and it’s

optional (hence the “?” in the type).

You can define a type as a TypeScript interface:

interface IMyProps {

text?: string; // an optional text field

myFunc: (count: number) => void; // a required function

myObj: ISomeClass; // an object whose type is defined by the inteface ISomeClass

}

The nice thing about the function declaration for myFunc

is that the caller has to match the signature of the definition. Passing zero parameters to myFunc will result in a compile-time

error. If you decide you don’t care about the function signature, you could also

declare myFunc as a Function. Or even any, if you were really lazy.

Although Bob Martin is usually a great source of advice on most things coding-related, he doesn’t like “I’s” in interfaces. Nor does he like interfaces in general. I happen to like both.

React uses a generic type to

define a ReactComponent class which uses the props and static types that you create. If you haven’t

used generic types before, they are a way of reusing one type definition with different

subtypes. For example, an Array type might be able to hold any kind of object, but

an Array<string> can only hold strings—and nothing else. A React Component

that’s defined like the following can only accept props that conform to IMyProps and use a state that

conforms to IMyState:

import * as React from "react";

class MyComponent extends React.Component {

// ...

}

Sometimes you’ll see definitions like class MyComponent extends React.Component<{}, {}>. This

means that this component doesn’t use props or state—they must be empty. class MyComponent extends React.Component<any, any> says

that you can pass anything for props and state and it will do no type checking.

Static, Private, Public

In TypeScript, propTypes, contextTypes, and defaultProps are a static properties,

meaning they’re created within the class definition, instead of on the prototype as in ES2015.

JavaScript still requires contortions to define

private and public members. Fortunately these are first-class parts of TypeScript. In

this example, onClick() is invisible outside the component.

Type Inference

It sounds like the word “Type” in TypeScript refers to the amount of extra typing to get all those type definitions in place. Fortunately, TypeScript is smart enough to infer a lot of the types so that you don’t have to explicitly provide them all the time. This is why when you pass in the console logging function, you can type this:

(count) => console.log(count)

…instead of this:

(count: number) => console.log(count)

Testing

I use airbnb’s enzyme for testing react components:

> yarn add enzyme --dev

# OR

> npm install enzyme --save-dev

Here are a couple tests. Note that nothing here is really TypeScript-specific. You can run them by typing yarn test (or npm test).

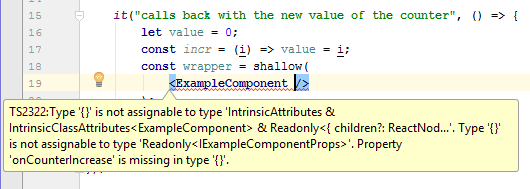

Here’s the thing: notice what happens if we forget to include our callback function—IntelliJ gives us a warning that it’s missing:

TypeScript makes propTypes unnecessary, because it will tell you at compile time—or while you’re typing it, if you’re using a TypeScript-aware editor—that you’re missing something. Or if you pass a function with the wrong signature (e.g. with missing parameters, or parameters of the wrong type), it will tell you that too.

More Reading

- Part 1: Getting Started with TypeScript and React

- Part 2: Simple React Components in TypeScript

- Part 3: Stateless React Components in TypeScript

- Part 4: React’s Higher Order Controls in TypeScript

- Coming soon: TypeScript with Redux; Testing & Continuous Deployment